If you want to know about the what is architecture or principles of design or theory of proportion, please click the link.

Form in architecture refers to the shape, structure, and arrangement of a building or object. It is an essential aspect of architectural design, as the form of a building can impact its functionality, aesthetic appeal, and overall impact on the environment. Form is often influenced by various factors such as cultural, historical, social, and technological contexts.

It can also be determined by practical considerations such as building use, climate, and construction methods. The relationship between form and function is a key consideration in architecture, as the form of a building must support and enhance its intended use.

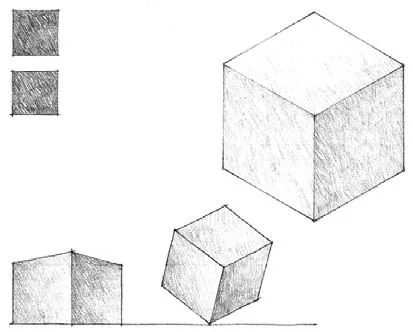

Form in architecture can be described as both two-dimensional (shape) and three-dimensional (volume).

1) Primary elements for creating form

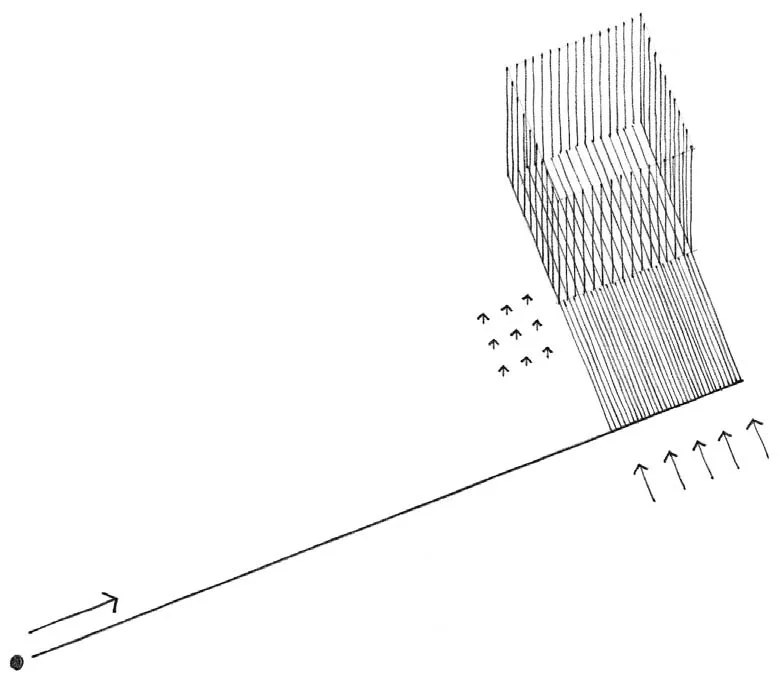

- All pictorial form begins with the point that sets itself in motion.

- The point moves and the line comes into being; the first dimension.

- If the line shifts to form a plane, we obtain a two-dimensional element.

- In the movement from plane to spaces, the clash of planes gives rise to body (three-dimensional).

- As conceptual elements, the point, line, plane, and volume are not visible except to the mind’s eye.

- While they do not actually exist, we nevertheless feel their presence.

- We can sense a point at the meeting of two lines, a line marking the contour of a plane, a plane enclosing a volume, and the volume of an object that occupies space.

- When made visible to the eye on paper or in three-dimensional space, these elements become form with characteristics of material, shape, size, color, and texture.

- As we experience these forms in our environment, we should be able to perceive in their structure, the existence of the primary elements of point, line, plane, and volume.

2) Architectural form

- Architectural form is the point of contact between mass and space. Architectural forms, textures, materials, modulation of light and shade, color, all combine to inject a quality or spirit that articulates space.

- The quality of the architecture will be determined by the skill of the designer in using and relating these elements, both in the interior spaces and in the spaces around buildings.

- Form is an inclusive term that has several meanings. It may refer to an external appearance that can be recognized, as that of a chair or the human body that sits in it.

- It may also refer to a particular condition in which something acts or manifests itself, as when we speak of water in the form of ice or steam. Form suggests reference to both internal structure and external outline and the principle that gives unity to the whole.

In addition to its visual impact, form can also affect a building’s energy efficiency and sustainability. For example, the orientation and shape of a building can impact the amount of natural light it receives, while the use of shading and insulation can impact its thermal performance.

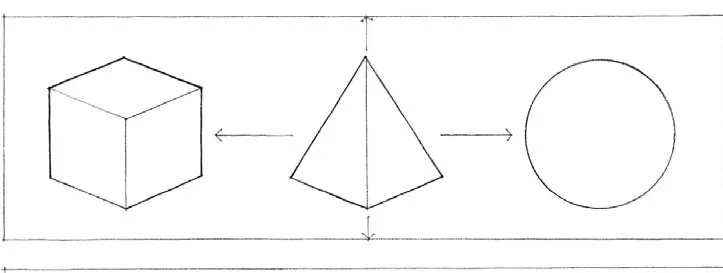

Form characteristics are Shape Size, texture, color, and arrangement.

The characteristic outline or surface configuration of a particular form. Shape is the principal aspect by which we identify and categorize forms.

- In addition to shape, forms have visual properties of:

i) Size

- The physical dimensions of length, width, and depth of a form.

- While these dimensions determine the proportions of a form, its scale is determined by its size relative to other forms in its context.

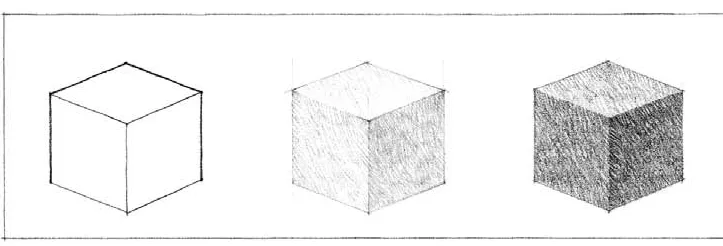

ii) Color

- A phenomenon of light and visual perception that may be described in terms of an individual’s perception of hue, saturation, and tonal value.

- Color is the attribute that most clearly distinguishes a form from its environment.

- It also affects the visual weight of a form.

iii) Texture

- The visual and especially tactile quality given to a surface by the size, shape, arrangement, and proportions of the parts. Texture also determines the degree to which the surfaces of a form reflect or absorb incident light.

- Forms also have relational properties that govern the pattern and composition of elements:

iv) Position

- The location of a form relative to its environment or the visual field within which it is seen.

v) Orientation

- The direction of a form relative to the ground plane, the compass points, other forms, or to the person viewing the form.

vi) Visual Inertia

- The degree of concentration and stability of a form.

- The visual inertia of a form depends on its geometry as well as its orientation relative to the ground plane, the pull of gravity, and our line of sight.

- Shape also refers to the characteristic outline of a plane figure or the surface configuration of a volumetric form.

- It is the primary means by which we recognize, identify, and categorize particular figures and forms.

- Our perception of shape depends on the degree of visual contrast that exists along the contour separating a figure from its ground or between a form and its field.

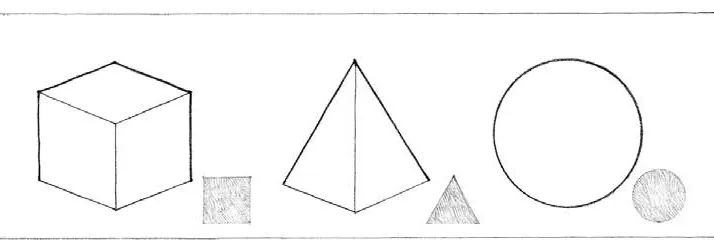

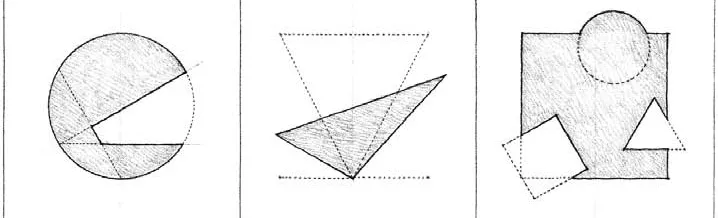

3) Primary Shape

- Gestalt psychology affirms that the mind will simplify the visual environment in order to understand it.

- Given any composition of forms, we tend to reduce the subject matter in our visual field to the simplest and most regular shapes.

- The simpler and more regular a shape is, the easier it is to perceive and understand.

- From geometry, we know the regular shapes to be the circle, and the infinite series of regular polygons that can be inscribed within it. Of these, the most significant are the primary shapes: the circle, the triangle, and the square.

Circle

- A plane curve every point of which is equidistant from a fixed point within the curve.

Triangle

- A plane figure bounded by three sides and having three angles.

Square

- A plane figure having four equal sides and four right angles.

- In the transition from the shapes of planes to the forms of volumes is situated the realm of surfaces. Surface first refers to any figure having only two dimensions, such as a flat plane. The term, however, can also refer to a curved two-dimensional locus of points defining the boundary of a three-dimensional solid. There is a special class of the latter that can be generated from the geometric family of curves and straight lines.

- This class of curved surfaces include the following: Cylindrical surfaces, Translational surfaces, Ruled surfaces, Rotational surfaces, Paraboloids, Hyperbolic paraboloids

4) Primary solids

“…Cubes, Cones, Spheres, Cylinders, or Pyramids are the great primary forms that light reveals to advantage; the image of these is distinct and tangible within us and without ambiguity. It is for this reason that these are beautiful forms, the most beautiful forms.” Le Corbusier

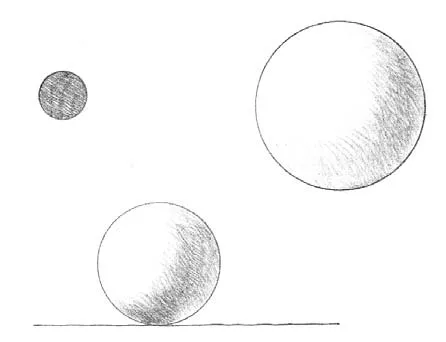

i) Sphere

- A solid generated by the revolution of a semicircle about its diameter, whose surface is at all points equidistant from the center.

- A sphere is a centralized and highly concentrated form.

ii) Cylinder

- A solid generated by the revolution of a rectangle about one of its sides.

- A cylinder is centralized about the axis passing through the centers of its two circular faces.

- Along this axis, it can be easily extended.

- The cylinder is stable if it rests on one of its circular faces; it becomes unstable when its central axis is inclined from the vertical.

iii) Cone

- A solid generated by the revolution of a right triangle about one of its sides.

- Like the cylinder, the cone is a highly stable form when resting on its circular base, and unstable when its vertical axis is tipped or overturned.

- It can also rest on its apex in a precarious state of balance.

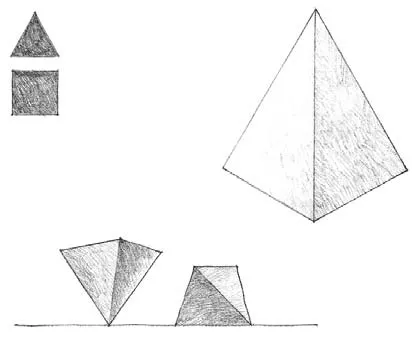

iv) Pyramid

- A polyhedron having a polygonal base and triangular faces meeting at a common point or vertex.

- The pyramid has properties similar to those of the cone.

- Because all of its surfaces are flat planes, however, the pyramid can rest in a stable manner on any of its faces.

- While the cone is a soft form, the pyramid is relatively hard and angular.

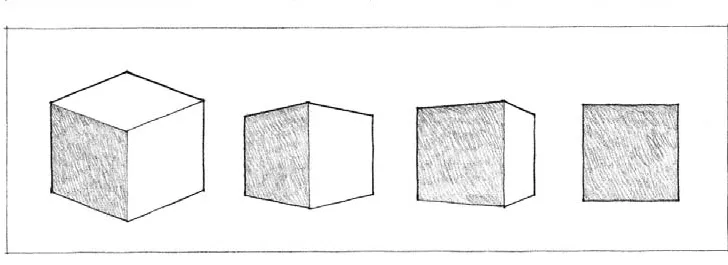

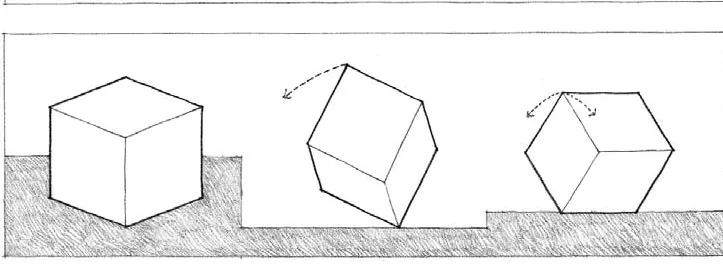

v) Cube

- A prismatic solid bounded by six equal square sides, the angle between any two adjacent faces being a right angle.

- Because of the equality of its dimensions, the cube is a static form that lacks apparent movement or direction.

- It is a stable form except when it stands on one of its edges or corners.

- Even though its angular profile is affected by our point of view, the cube remains a highly recognizable form.

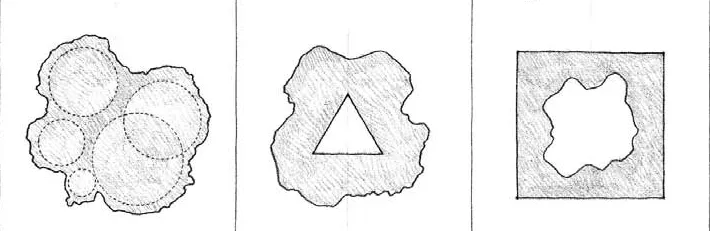

5) Regular and Irregular forms

i) Regular

- Regular forms refer to those whose parts are related to one another in a consistent and orderly manner.

- They are generally stable in nature and symmetrical about one or more axes.

- The sphere, cylinder, cone, cube, and pyramid are prime examples of regular forms.

- Forms can retain their regularity even when transformed dimensionally or by the addition or subtraction of elements.

- From our experiences with similar forms, we can construct a mental model of the original whole even when a fragment is missing, or another part is added.

ii) Irregular

- Irregular forms are those whose parts are dissimilar in nature and related to one another in an inconsistent manner.

- They are generally asymmetrical and more dynamic than regular forms.

- They can be regular forms from which irregular elements have been subtracted or result from an irregular composition of regular forms. Since we deal with both solid masses and spatial voids in architecture, regular forms can be contained within irregular forms.

- In a similar manner, irregular forms can be enclosed by regular forms.

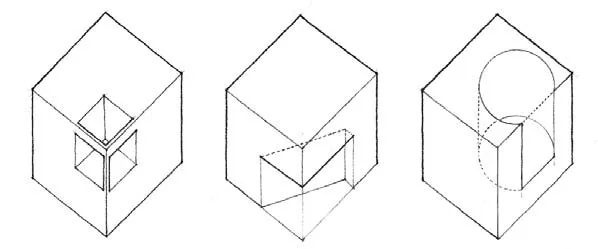

6) Transformation of form

i) Dimensional Transformation

- A form can be transformed by altering one or more of its dimensions and still retain its identity as a member of a family of forms.

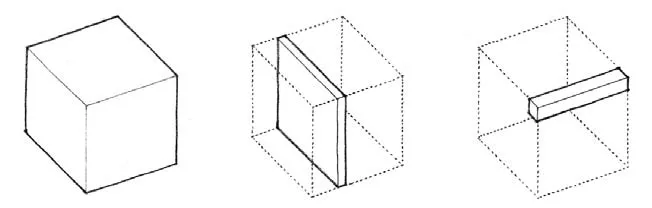

ii) Subtractive Transformation

- A form can be transformed by subtracting a portion of its volume.

- Depending on the extent of the subtractive process, the form can retain its initial identity or be transformed into a form of another family.

iii) Additive Transformation

- A form can be transformed by the addition of elements to its volume.

- The nature of the additive process and the number and relative sizes of the elements being attached determine whether the identity of the initial form is altered or retained.

iv) Subtractive Form

- We search for regularity and continuity in the forms we see within our field of vision.

- If any of the primary solids is partially hidden from our view, we tend to complete its form and visualize it as if it were whole because the mind fills in what the eyes do not see.

- In a similar manner, when regular forms have fragments missing from their volumes, they retain their formal identities if we perceive them as incomplete wholes.

- We refer to these mutilated forms as subtractive forms.

v) Additive form

- While a subtractive form results from the removal of a portion of its original volume, an additive form is produced by relating or physically attaching one or more subordinate forms to its volume.

- Additive forms resulting from the accretion of discrete elements can be characterized by their ability to grow and merge with other forms.

- For us to perceive additive groupings as unified compositions of form

- Categorize additive forms according to the nature of the relationships that exist among the component forms as well as their overall configurations.

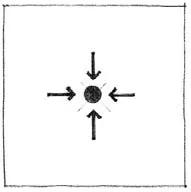

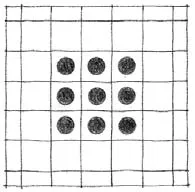

Centralized Form

- A number of secondary forms clustered about a dominant, central parent-form.

Linear Form

- A series of forms arranged sequentially in a row.

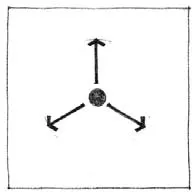

Radial Form

- A composition of linear forms extending outward from a central form in a radial manner.

Clustered Form

- A collection of forms grouped together by proximity or the sharing of a common visual trait.

Grid Form

- A set of modular forms related and regulated by a three-dimensional grid.

7) Articulation of form

Articulation refers to the manner in which the surfaces of a form come together to define its shape and volume. An articulated form clearly reveals the precise nature of its parts and their relationships to each other and to the whole. Its surfaces appear as discrete planes with distinct shapes and their overall configuration is legible and easily perceived.

In a similar manner an articulated group of forms highlights the joints between the constituent parts in order to visually express their individuality.

A form in architecture can be articulated or defined by various techniques, including:

- Modulation: The use of changes in scale or rhythm to create a sense of movement and structure in a building’s form.

- Hierarchy: The arrangement of elements in a building based on their importance, with larger or more prominent elements being used to define the overall form.

- Symmetry: The balance of elements in a building about a central axis, creating a sense of stability and order.

- Asymmetry: The uneven distribution of elements in a building, creating a sense of dynamism and movement.

- Repetition: The repeated use of similar elements, such as windows or columns, to create a sense of unity and rhythm in a building’s form.

- Progression: The gradual change in elements, such as size or shape, to create a sense of movement and flow in a building’s form.

- Termination: The use of specific elements, such as a roof or facade, to define the ends of a building and create a sense of closure.

- Accentuation: The use of contrasting elements, such as color or texture, to highlight specific parts of a building and draw attention to its form.

These techniques can be used by architects to emphasize the form of a building, creating visual interest and shaping the way people experience and respond to it. By carefully articulating the form of a building, architects can create dynamic, expressive, and functional structures that enrich the built environment.

In conclusion, form is a crucial element of architecture that shapes the built environment and impacts our experience of it. Architects use form to create visually appealing and functional buildings that respond to the needs and context of the people who use them.