If you want to know about the acoustics in auditorium or acoustics in cinema or introduction of acoustics, please click the link.

Acoustics in landscape refers to the study of how sound behaves in outdoor environments, including how it travels, is reflected and absorbed by natural and man-made features, and is affected by weather conditions. Understanding acoustics in landscape is important for a variety of reasons, including designing spaces for optimal sound quality, mitigating noise pollution, and preserving natural soundscapes.

1) Acoustics in landscape (Introduction)

- The science of sound control in the landscape involves much more than the simple quantification of data.

- The quality of sound may be as important as the quantity of sound. Some sounds can have profound psychological effects on people.

- For example, the constant drone of cars on the highway is rarely as offensive as the squealing of brakes at an intersection.

Acoustic variables:

Three acoustic variables to address when attempting to minimize noise problems in the landscape are:

- The source of sound;

- The path and distance of sound transmission; and

- The receiver of sound.

Sources of sound:

- Most noise can be modified by acoustical treatment at its source; however; this is often not as economically feasible as control of noise by various landscape planning techniques.

Path and distance of sound transmission:

- A valley or a downwind site, for example, can make any development in these areas more susceptible to noise.

Receiver of sound:

- People who are accustomed to quiet landscapes are significantly less tolerant of noise than people accustomed to suburban of urban environments.

- Masking of noise can sometimes be accomplished by introducing pleasant sounds, such as the sound of flowing water or rustling leaves.

2) Sound barriers

i) Sound barriers

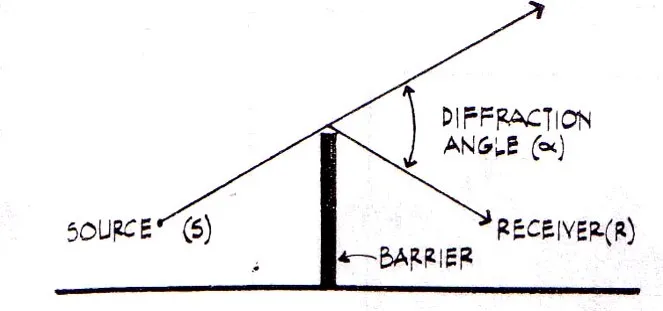

The degree of attenuation provided by a noise barrier is mainly a functional of:

- The diffraction angle alpha through which the sound path must be bent in order to get from source to receiver; and

- The frequency of the sound source.

ii) Distance (placement of barrier)

- A sound barrier should be erected as close as possible to either the noise source or the receiving position in order to maximize the diffraction angle.

iii) Height of the barrier

- The minimum height of the barrier should be such that the line of sight between source and receiver is interrupted.

iv) Physical mass of a barrier (material)

- It should have a surface weight, or mass, of at least 6 to 12 kg/m2. A noise level reduction of 10 to 15 db is possible with such a barrier; a reduction of 5 to 10 db is considered to be most cost-effective.

v) Continuity of barrier

- No gaps or holes should be present in a noise barrier. It must be effectively airtight.

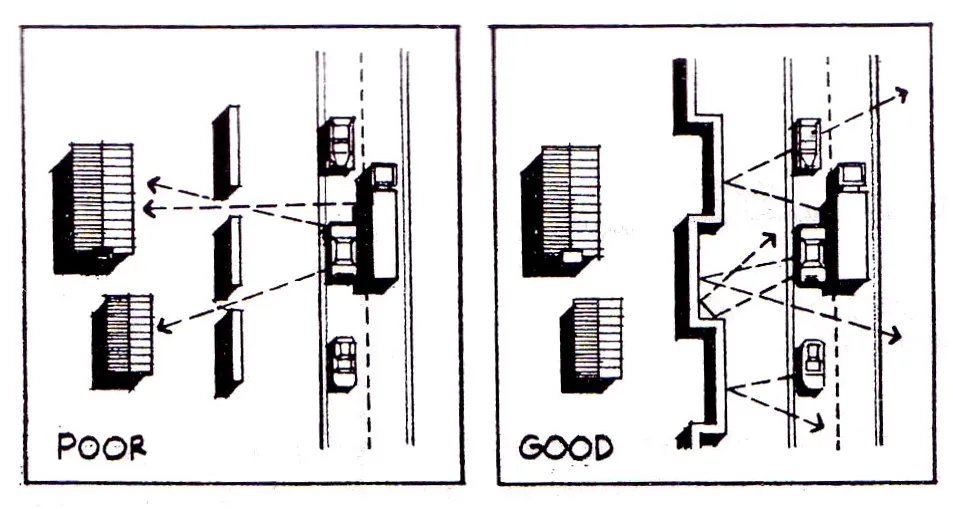

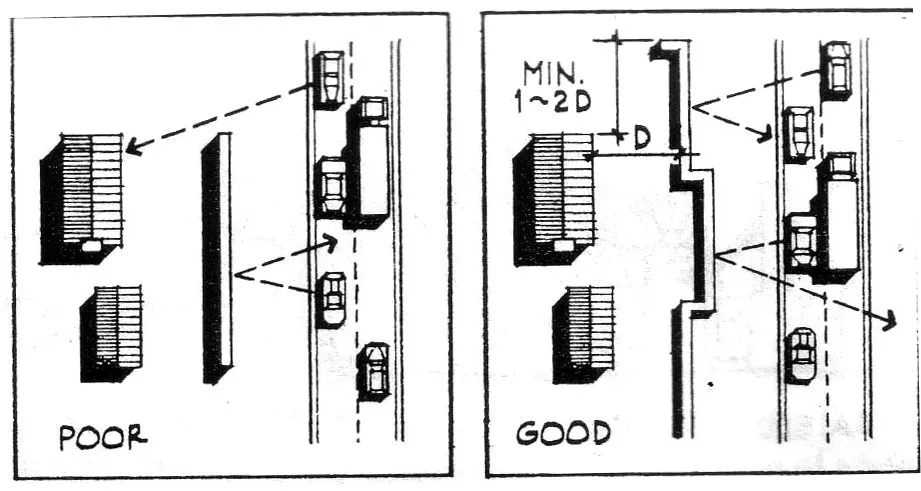

vi) Length of barrier

- The length of the noise barrier should be at least 1 to 2 times the distance between the barrier and the protected structure to minimize sound diffraction around the ends of the barrier.

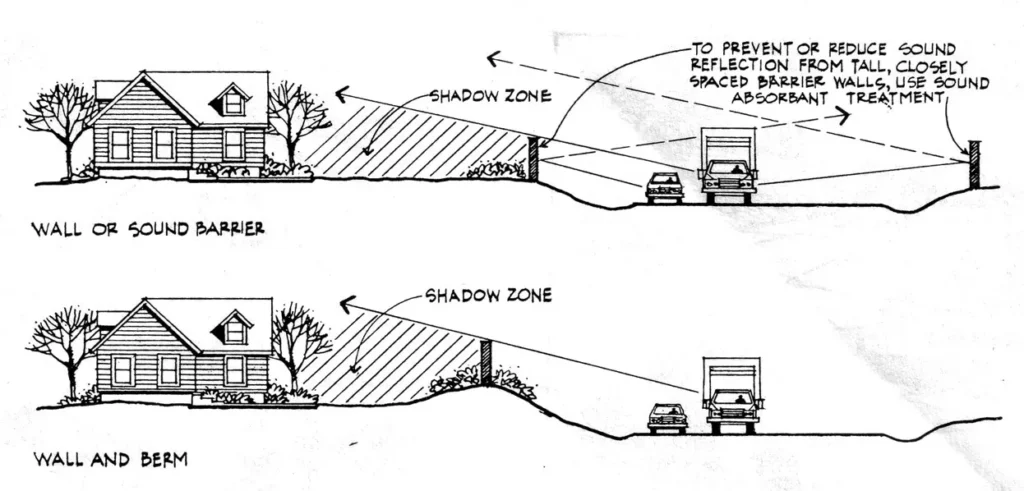

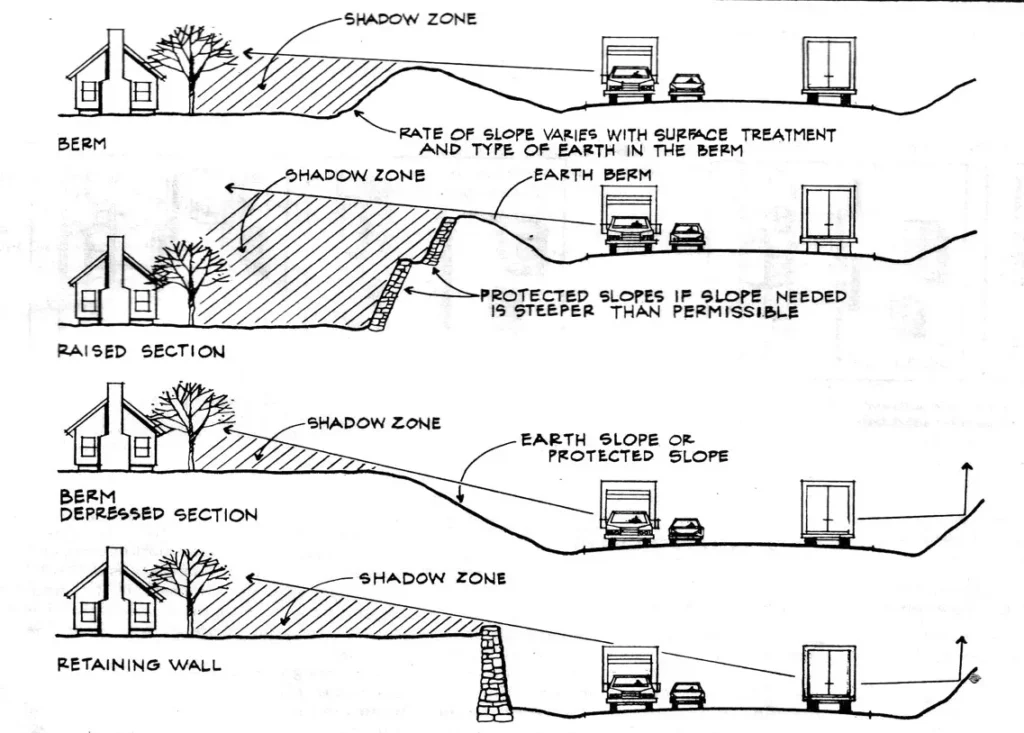

vii) Earth berms

- The careful design and situation of earth berms can be an effective way of reducing noise from traffic or construction operations.

- Berms can either be temporary or can remain as a permanent feature of landscape.

viii) Barrier walls and earth berms

- Barrier walls can be used separately or in combination with earth berms to minimize noise levels.

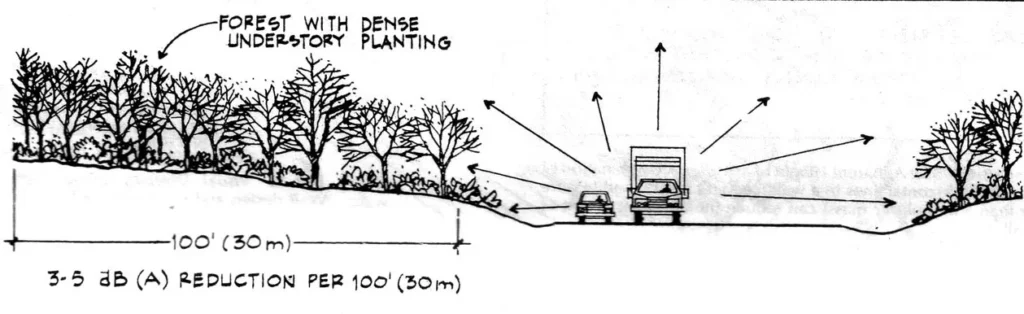

ix) Vegetation

- The type of ground surface over which sound travels does have a substantial effect on sound attenuation, particularly when traveling over large distances.

- Areas covered with grass or other types of groundcover are more absorptive than hard, paved surfaces, which tend to reflect the sound.

- Taller plantings, such as hedges or shallow screen plantings will not significantly reduce actual noise levels.

- However, dense plantings of trees with an under story of shrubs can result in a reduction of 3 to 5 db per 100’(300 m) of depth from the sound.

3) Aesthetics in sound barriers

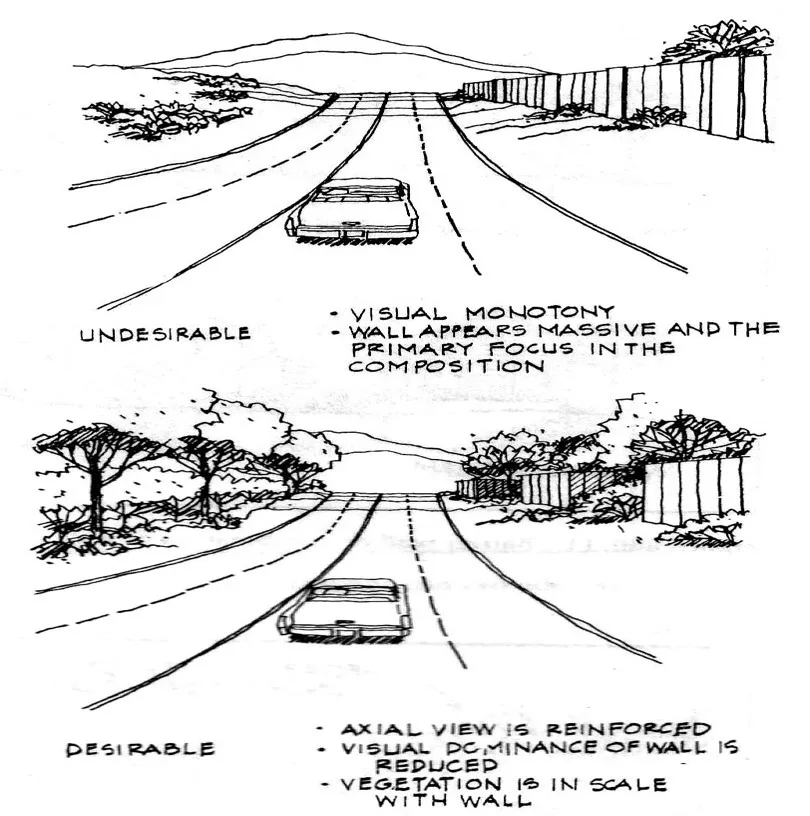

i) Aesthetic issues

- Noise barriers along highway corridors should be seen as elements which define and enclose linear space.

- Visual perception in these corridors will be influenced by travel speed, light, spatial quality, location, physical distances, roadways and viewing heights.

ii) Mass

- Massive unrelieved forms can sometimes arouse uncomfortable feelings of claustrophobia or insecurity.

- The apparent mass of a noise barrier can be minimized by means of stepped wall sections, staggered alignments, plantings, articulation and integration with landform.

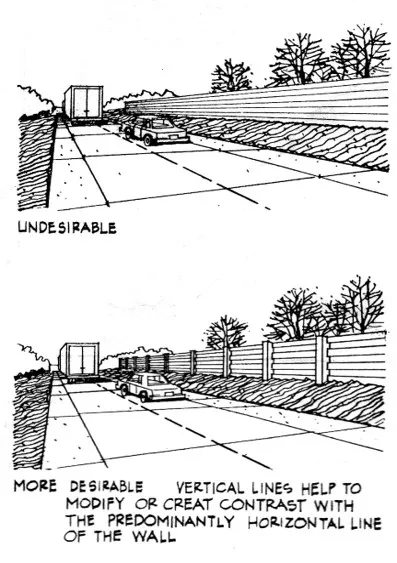

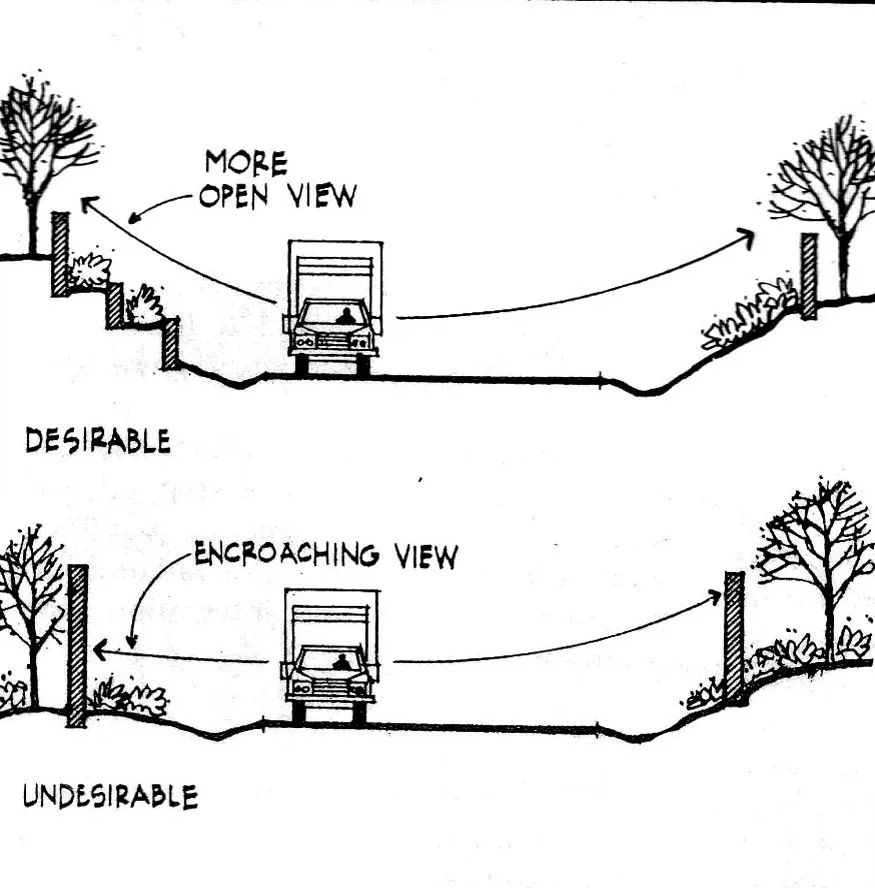

iii) Planes

- In highway design, barriers can provoke feelings of excessive enclosure or give a monotonous appearance.

- In such cases, it is necessary to create variety and interest in the design of barriers and related landscape.

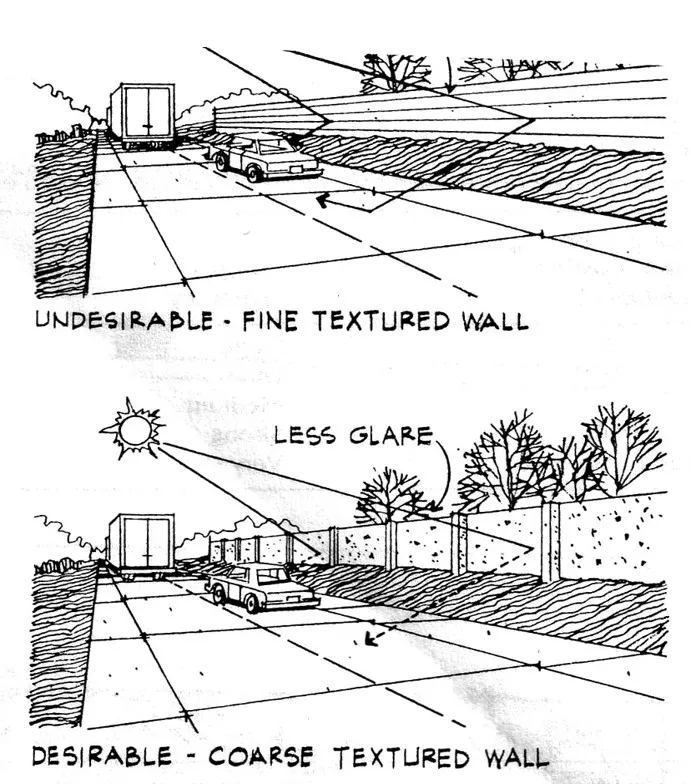

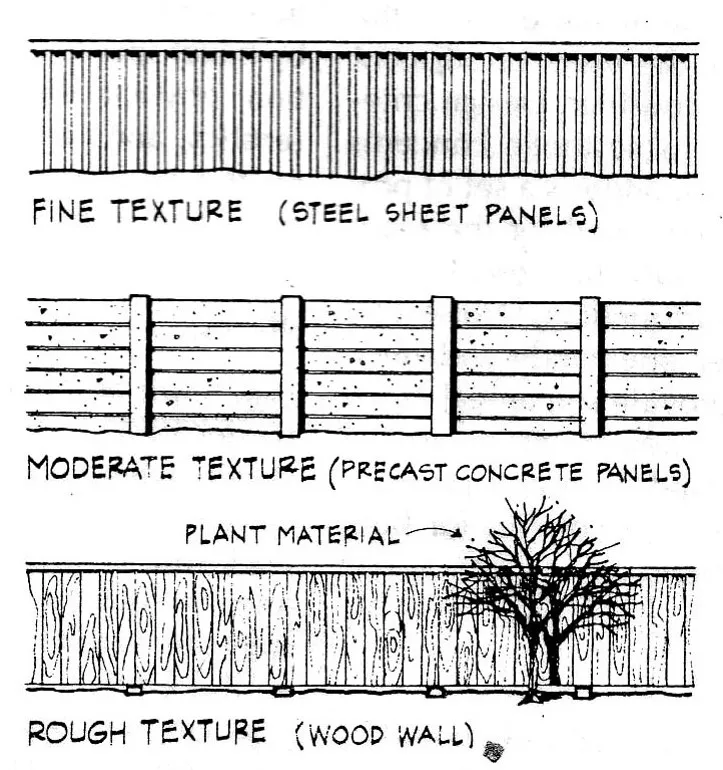

iv) Texture

- Increased speed of travel, angle of vision and distance from an object all tends to decrease the apparent degree of texture.

- Surfaces that are relatively smooth, not only cause undesirable reflections of light and sound but also promote monotony in the landscape.

v) Stepped-back wall

- A wall which steps back can open up the view for the motorists and provide psychological relief from feelings of tight enclosure.

vi) Wall texture

- Fine textured walls are often monotonous and may cause problems of reflective glare.

Overall, acoustics in landscape is an important field that has applications in a variety of areas, including design, environmental conservation, and public health.